NOTES & STORIES |

Beethoven Sonata No. 10 for Piano and Violin in G Major, Op. 96 |

250 years after his birth, and after 200-plus years of hagiography, running from the ecstasies of Friedrech Nietzsche to the musings of Charles M. Schulz, it is worth mentioning that it was not easy —let alone great—to be Beethoven. “Everything I do apart from music is badly done and stupid,” he wrote, and he had a point. He did plenty of foolish things. Socially, financially, and personally, he left considerable wreckage behind him. All in all, Beethoven seems to have had trouble navigating the world. He could not multiply. He could not dance. His father drank, and his mother died while he was away. His courtships failed. His deafness stands not only as a historical irony or challenge; the pain and solitude of it affected his entire life.

This is all to say that Beethoven was a real person, and that his suffering was also real. He managed nonetheless to forge a collection of highly unusual musical works, and these works continue to deliver an unusually powerful message to his readers and hearers. In the dots, curves, and scratches of his pages, he drew strange maps for the contours of experience, in musical works which—strange to say—continue to make sense.

Ludwig van Beethoven was born 250 years ago on December 16, 1770. Or maybe it was the 17th—nobody really seems to know which. Thanks to some early fudging on his birth year, which was meant to exaggerate his prodigiousness, Beethoven seems to have been unclear even on the year in which he was born, let alone the day.

This is all to say that Beethoven was a real person, and that his suffering was also real. He managed nonetheless to forge a collection of highly unusual musical works, and these works continue to deliver an unusually powerful message to his readers and hearers. In the dots, curves, and scratches of his pages, he drew strange maps for the contours of experience, in musical works which—strange to say—continue to make sense.

Ludwig van Beethoven was born 250 years ago on December 16, 1770. Or maybe it was the 17th—nobody really seems to know which. Thanks to some early fudging on his birth year, which was meant to exaggerate his prodigiousness, Beethoven seems to have been unclear even on the year in which he was born, let alone the day.

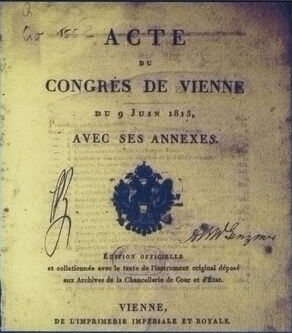

The years around 1812, when Beethoven was in his early thirties, were loud ones in Europe. After vast upheaval, Napoleon was defeated in Russia, Vittoria, and (finally) Waterloo. Vienna filled with diplomats and aristocrats for the 1814-15 Congress of Vienna, which established a geopolitical path for post-Napoleonic Europe and left storied trails of private intrigues and public gatherings. Beethoven played his part in the pageantry, writing Wellington’s Victory (also known as the Battle of Vittoria) and Der glorreiche Augenblick (The Glorious Moment).

But things had been growing ever quieter for Beethoven, whose fame and fate-motifs were proving ineffective against his essential loneliness and deafness. And so he came to write music for the interior life—the complex, complete, and infinite interior of one who is forced to listen to thought, and who hears it with strange clarity. In a letter to the Archduke Rudolph, he wrote, ‘I can have recourse to no one but myself for aid, and can find help in my own head alone’. And, by default, this interiority would become the subject of his music. There was little choice.

It wasn’t that he didn’t try to do better. 1812 was the year of his only surviving letter to an ‘immortal beloved’—a woman who does indeed seem to have existed, and who seems likely to have been (by the latest guess) one of three candidates: Josephine Deym, Antonie Brentano, or Bettina Brentano. But whoever was involved, and whatever the depth of the affair, it most certainly had no happy ending. With this failure Beethoven's romantic aspirations seem to have ended. A week later, he wrote the Archduke: "Hence I am living--alone--alone! alone!" Just about the same time as his hopes for meeting a partner in life were extinguished, he met with Goethe for the first time, and they don’t seem to have gotten along so well, either. Beethoven was 42 years old.

That December, the Archduke Rudolph and the violinist Pierre Rode gave the premiere of the Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major, Op. 96.

But things had been growing ever quieter for Beethoven, whose fame and fate-motifs were proving ineffective against his essential loneliness and deafness. And so he came to write music for the interior life—the complex, complete, and infinite interior of one who is forced to listen to thought, and who hears it with strange clarity. In a letter to the Archduke Rudolph, he wrote, ‘I can have recourse to no one but myself for aid, and can find help in my own head alone’. And, by default, this interiority would become the subject of his music. There was little choice.

It wasn’t that he didn’t try to do better. 1812 was the year of his only surviving letter to an ‘immortal beloved’—a woman who does indeed seem to have existed, and who seems likely to have been (by the latest guess) one of three candidates: Josephine Deym, Antonie Brentano, or Bettina Brentano. But whoever was involved, and whatever the depth of the affair, it most certainly had no happy ending. With this failure Beethoven's romantic aspirations seem to have ended. A week later, he wrote the Archduke: "Hence I am living--alone--alone! alone!" Just about the same time as his hopes for meeting a partner in life were extinguished, he met with Goethe for the first time, and they don’t seem to have gotten along so well, either. Beethoven was 42 years old.

That December, the Archduke Rudolph and the violinist Pierre Rode gave the premiere of the Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major, Op. 96.

While it’s impossible to make strict delineations, there can be no question that the Piano and Violin Sonata in G Major, Op. 96 (1812) stands either at the beginning of a "late" period or at the very end of a "middle" one. Many of the markers of Beethoven’s later compositions are there: the distracted pastoral lilt of an interior landscape; the unreachable fantasy of a duet; the inconclusive harmonies; the melting variations; the odd fugues.

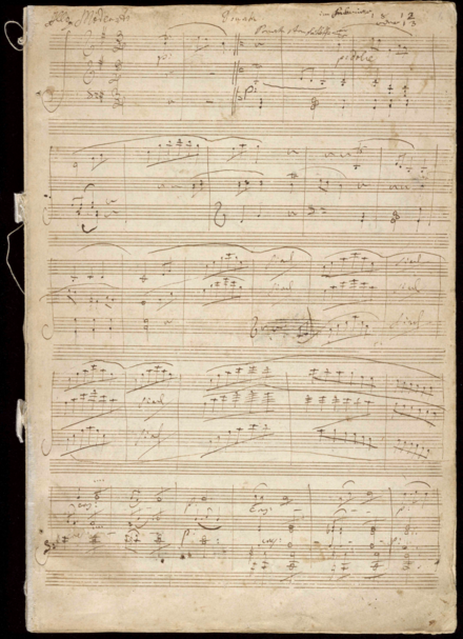

Even from a visual standpoint, the manuscript of the sonata can give an idea of what an ‘interior pastoral’ might contain. It is light, it is clear, and it flows. Long slurs glide across the page. The opening figure in the violin could be a bird call as much as it could be a vocal lyric. Most of the dialogue between violin and piano is gentle or breezily entwined. The mood is gentle, the manner lightly surprising.

The second movement is oddly reminiscent of the second movement of the Fifth ("Emperor") Piano Concerto, but it has no epic surrounding it: the violin sonata’s Adagio espressivo stands calmly in the midst of peace and brightness. It ventures only further inward.

Even in the scherzo, which is here, as usual for Beethoven, an opportunity for stubborn, rustic, contrarian moods and rhythms, he finds a flying, flowing escape in the middle section, and it concludes with a surprisingly peaceful shift to the last movement.

Even from a visual standpoint, the manuscript of the sonata can give an idea of what an ‘interior pastoral’ might contain. It is light, it is clear, and it flows. Long slurs glide across the page. The opening figure in the violin could be a bird call as much as it could be a vocal lyric. Most of the dialogue between violin and piano is gentle or breezily entwined. The mood is gentle, the manner lightly surprising.

The second movement is oddly reminiscent of the second movement of the Fifth ("Emperor") Piano Concerto, but it has no epic surrounding it: the violin sonata’s Adagio espressivo stands calmly in the midst of peace and brightness. It ventures only further inward.

Even in the scherzo, which is here, as usual for Beethoven, an opportunity for stubborn, rustic, contrarian moods and rhythms, he finds a flying, flowing escape in the middle section, and it concludes with a surprisingly peaceful shift to the last movement.

The last movement is a set of variations. Beethoven wrote fantastic variations. As both an improviser and a composer who liked to keep ‘the whole in view’, the form suited him well. Variations (as in jazz standards) allow for wild flights of music above recognizable roots. Even in his younger years, Beethoven would carry his variations up to the edge of their thematic reference, and here he begins to depart further, allowing the sections to drift into one another and make strange detours (see the analysis section for more about this). The piano sonatas Op. 109 and 111 take these techniques still further—variations became almost a game of hide-and-seek, the theme an enigma of memory. In the manuscript of Op. 96 one can see how Beethoven struggled with the most distant variation, no. 7. But in this work, at least, a kind of simplicity wins out. A strange light and bright prevails in the strange, uncertain refuge of abstraction.

The sonata Op. 96 was written for the French violinist Pierre Rode. Violinists know of Pierre Rode as the author of a book of 24 Caprices for Violin in all keys, published in 1815, not long after the Op. 96 Sonata. Rode's works are surprisingly delicate, flowing and operatic considering their pedagogical purposes, and their figuration seems not only idiomatic to the time, but perhaps even reflects those in Beethoven’s sonata.

Lastly, there is one delicate detail in the first publication of Rode’s Caprices for violin that contains quite a lot of the flavor of the time. At the beginning of the first caprice, it is stated that the tempo is 84 beats per minute du Métronome de Maelzel. Johann Nepomuk Maelzel was a musical inventor and engineer who manufactured a very successful metronome. He also commissioned and to some extent even co-wrote Wellington’s Victory (largely regarded as Beethoven’s worst piece), and revived the fraudulent chess-playing Mechanical Turk (which defeated Napoleon at chess, and which lives on as the name of a substantial segment of Amazon Web Services). Many of Beethoven's metronome markings are followed by the letters "M. M.": 'Maelzels Metronome'. And last, this same Maelzel developed a set of ear trumpets for Ludwig van Beethoven in 1813, as the composer made ever-more desperate attempts to maintain aural contact with the world outside. This desperation to know the outside, strangely, is our point of closest contact with what he wrote. The interior is our reference, even when the exterior is ours to hear. We all have our late period; it is perpetual, and may even be forced upon us—should we find ourselves also, somehow, locked inside.

© Timothy Summers

© Timothy Summers