Audio & Insights |

Beethoven String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132

|

Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart

Sacred song of thanks from a convalescent to the divine, in the Lydian mode.

Sacred song of thanks from a convalescent to the divine, in the Lydian mode.

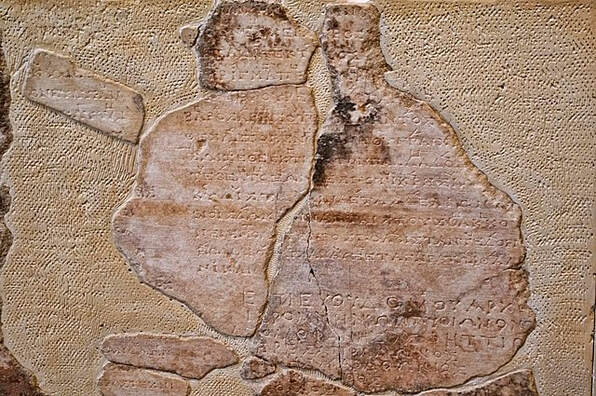

Second Delphic Hymn (128 BCE), photograph by Michael Nicht (Creative Commons)

Second Delphic Hymn (128 BCE), photograph by Michael Nicht (Creative Commons)

Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart would be a heavy title even if it weren't written in German. The words Heilig (holy, blessed, sacred) and Gottheit (deity, divinity) command metaphysical attention, and the image of a convalescent making a recovery worthy of divine acknowledgement suggests that the author has himself returned from the edge.

The addition of Lydischen tonart to the title of the movement seems a bit odd at first—a bit technical, a bit esoteric. But it has practical consequences. First, the intimation of antiquity suggests that eternal matters are at hand, and that the music should read with appropriate gravity. Second, the matter of what seems 'old' and what seems 'new' can be crucially important to the meaning, reception, and performance of any music, from "classical" music to "classic rock". So the simple presence of age brings audible consequence and meaning.

The title is memorable, and the movement, as if on cue, has emerged as a historically outstanding example of Beethoven's late works. This is perhaps partly coincidence and rhyme, since Heiliger Dankgesang is so aurally near to Heiligenstadt Testament, the private document from twenty-plus years before, in which Beethoven laid out his grief and rage at encroaching deafness, and declared his profound dedication to continue with his art in spite of it. (Note: Heiligenstadt is not an unusually holy place, holy though it sounds: it is a suburban district of Vienna.) But the fame of this movement from the string quartet does not arise from mere rhyme and meme: it gives a window onto Beethoven's ability to draw his own internal struggles in the strange language of tonal music. It is very powerful music, and does not take its name lightly. Many have turned to it in their own times of need.

There is also a rather baffling historical curiosity, worth mentioning perhaps only here in the context of the conspiratorial, hyperlinked, ahistorical and metahistorical internet. Carved in an ancient fragment of rock, there is a a Paean and Prosodion to the God, written in the Lydian tonos in 128 BCE. It is attributed to an Athenian named Limenios and dedicated to Apollo (god of both music and healing). This carving is 'the earliest unambiguous surviving example of notated music from anywhere in the western world whose composer is known by name.' (according to Wikipedia Delphic Hymns). Its text translates thus:

The addition of Lydischen tonart to the title of the movement seems a bit odd at first—a bit technical, a bit esoteric. But it has practical consequences. First, the intimation of antiquity suggests that eternal matters are at hand, and that the music should read with appropriate gravity. Second, the matter of what seems 'old' and what seems 'new' can be crucially important to the meaning, reception, and performance of any music, from "classical" music to "classic rock". So the simple presence of age brings audible consequence and meaning.

The title is memorable, and the movement, as if on cue, has emerged as a historically outstanding example of Beethoven's late works. This is perhaps partly coincidence and rhyme, since Heiliger Dankgesang is so aurally near to Heiligenstadt Testament, the private document from twenty-plus years before, in which Beethoven laid out his grief and rage at encroaching deafness, and declared his profound dedication to continue with his art in spite of it. (Note: Heiligenstadt is not an unusually holy place, holy though it sounds: it is a suburban district of Vienna.) But the fame of this movement from the string quartet does not arise from mere rhyme and meme: it gives a window onto Beethoven's ability to draw his own internal struggles in the strange language of tonal music. It is very powerful music, and does not take its name lightly. Many have turned to it in their own times of need.

There is also a rather baffling historical curiosity, worth mentioning perhaps only here in the context of the conspiratorial, hyperlinked, ahistorical and metahistorical internet. Carved in an ancient fragment of rock, there is a a Paean and Prosodion to the God, written in the Lydian tonos in 128 BCE. It is attributed to an Athenian named Limenios and dedicated to Apollo (god of both music and healing). This carving is 'the earliest unambiguous surviving example of notated music from anywhere in the western world whose composer is known by name.' (according to Wikipedia Delphic Hymns). Its text translates thus:

Come ye to this twin-peaked slope of Parnassos with distant views, [where dancers are welcome], and [lead me in my songs], Pierian Goddesses who dwell on the snow-swept crags of Helikon. Sing in honour of Pythian Phoebus, golden-haired, skilled archer and musician, whom blessed Leto bore beside the celebrated marsh, grasping with her hands a sturdy branch of the grey-green olive tree in her time of travail.

Landels, John Gray, 1999, p237. Music in Ancient Greece and Rome. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-04284-0.

Given the particularity of Beethoven's title, it seems unusual that there should be such a similarly named piece of music with such an explicitly similar tonal system, hewn in an ancient rock. It is rather tempting to imagine that Beethoven somehow knew of this mysterious musical source.

There is a fatal flaw, though: this Greek rock fragment was discovered in 1893, and the string quartet dates from 1825. The idea of a paean cannot have been not so unusual as an poetic archaism, and perhaps some hint of this title appeared to Beethoven in a contemporary text about ancient musical traditions. But what an odd collection of incidents and accidents! In the end, we can only assume that Beethoven was applying his interest in ancient music, and that there was a palpable meaning in his summoning ancient technique and atmosphere for his then-contemporary purposes. The rest is history, conjecture, and hypertext.

There is a fatal flaw, though: this Greek rock fragment was discovered in 1893, and the string quartet dates from 1825. The idea of a paean cannot have been not so unusual as an poetic archaism, and perhaps some hint of this title appeared to Beethoven in a contemporary text about ancient musical traditions. But what an odd collection of incidents and accidents! In the end, we can only assume that Beethoven was applying his interest in ancient music, and that there was a palpable meaning in his summoning ancient technique and atmosphere for his then-contemporary purposes. The rest is history, conjecture, and hypertext.

Meanwhile, on Earth: the theme of The Simpsons (Danny Elfman, 1989) is also written in the Lydian mode. The third note of its melody is the tell-tale 'raised fourth' of the Lydian scale. That is only to say, beyond question, that the Lydian mode can bear many meanings and moods depending on its context. It needn't be so serious, or even archaic.

And meanwhile, for Ludwig van Beethoven in 1825, the years were indeed weighing heavily: his health failing, his social contacts decaying. His title contains only the words which he gave it. The rest we must imagine, amidst the rhymes and coincidences, as the work of someone who has constructed means to express the gratitude of one who has been gravely ill, and yet lived on to write more music, just as he had promised himself he would, back in Heiligenstadt.

And meanwhile, for Ludwig van Beethoven in 1825, the years were indeed weighing heavily: his health failing, his social contacts decaying. His title contains only the words which he gave it. The rest we must imagine, amidst the rhymes and coincidences, as the work of someone who has constructed means to express the gratitude of one who has been gravely ill, and yet lived on to write more music, just as he had promised himself he would, back in Heiligenstadt.

The Lydian Mode

Without delving too deeply into the whats and whys of modes—and whether they exist at all--here is a very brief introduction.

It works more or less like this: C major is the most 'pure', using the white keys of the piano, without sharps or flats. The Lydian mode uses the same keys, but starts its scale at F instead of C. The Lydian mode is the most upward-oriented of all the combinations of C major. If any other note were to go higher, the notes would begin to re-cluster and clump.

The Lydian mode lies at the heart of the analysis algorithm used on these pages, and has been important in twentieth century jazz composition and theory, most notably in the work of George Russell (Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization).

The colourful audio players contain measurements of harmonic content in the live audio, colouring harmonies which are close to one another in harmonic function as close on the visible spectrum. If you would like to learn more about these audio players, click here.

The Lydian mode lies at the heart of the analysis algorithm used on these pages, and has been important in twentieth century jazz composition and theory, most notably in the work of George Russell (Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization).

The colourful audio players contain measurements of harmonic content in the live audio, colouring harmonies which are close to one another in harmonic function as close on the visible spectrum. If you would like to learn more about these audio players, click here.

Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart

This work ought best not be interrupted, but for the curious, it is worth taking a look at it in five parts. To take it apart a little bit may increase its effectiveness when taken as a whole.

This work ought best not be interrupted, but for the curious, it is worth taking a look at it in five parts. To take it apart a little bit may increase its effectiveness when taken as a whole.

Molto Adagio

The first section stays heavily in the Lydian mode. As the intervals move, the essential space remains close to red (C Major - the conventional home) and pink (F Major - the home of the Lydian mode). The red stripe running along the bottom of the analysis traces this consistency, showing the Lydian mode to be a permutation of C Major.

Andante - Neue Kraft fühlend (feeling new strength)

The comparative brightness of this section is clear, as is its quicker motion. D Major predominates in yellow.

Molto Adagio

The lydian meditation returns.

Andante

The renewal of strength seems to be renewing life with it, bringing ornaments like new growth. It is extremely similar to the first Andante section, but has a few beautiful differences. (These tools can be used to compare the two sections.)

Molto Adagio

The Lydian meditation returns—interrupted, on one occasion by a hint of brightness within (where the lowest stripe turns to yellow, and then orange, thanks to a few upward-looking sharps in the score). It is sufficient to say that something seems to break. This can be seen from the dynamics in the waveform as much as from the harmony.

Above all, the changes in harmony and counterpoint carry heavy loads in this work, and bear these loads with and as much dignity and, for lack of a better word, seriousness as might ever be asked of music.

© Timothy Summers