Notes & Stories |

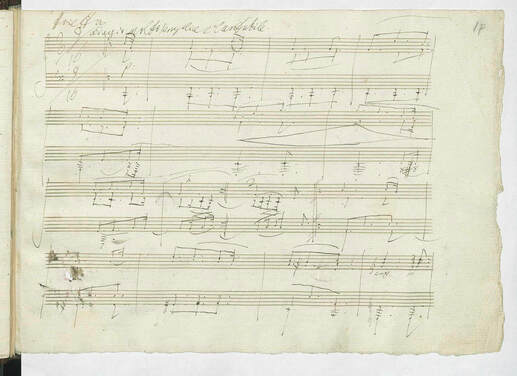

Beethoven Sonata for Piano in C minor, Op. 111 |

|

It is easy to become sentimental about artists’ late works, just as it is easy to become sentimental about their deaths—after which they seem to improve considerably, both as artists and as human beings. So if we consider the legendary Ludwig van Beethoven’s last piano sonata, a storm of temptingly powerful ideas can quickly appear: greatness, deafness, illness, futility, fate, loneliness, memory, posterity, mortality, and immortality, to name a few. Then, inevitably, there comes a reactionary impulse to reject these grand concepts as delusional, destructive or at the very least excessively sentimental, and to wonder at how all these pressures and thoughts and imaginary histories might have come to exert such force in the first place. An artist, some work, a life: how great can it all have been?

|

Perhaps we can set these mood swings of historical/biographical projection somewhat to the side, at least for a while. It seems rather hasty to discover only salvation or sin in historical memory. Perhaps there is some common-sense element to the hope that there should be transmissible meaning both in Beethoven's long experience and in the attention that his work has received. And perhaps it is not foolish or futile to seek meaning in the musical materials of someone who spent his time on Earth exploring the emotional meaning of materials. In the case of the Piano Sonata, Op. 111, this seems at least to be a sensible line of thought, because it is not just the person but the piece that comes to a very particular kind of end. The sonata’s material breaks; its wholeness surrenders; its memory slips; its systems collapse; and yet the sound of the work lives at the end. Op. 111 is not Beethoven's last piano work, but it is his last piano sonata, coming at the end of an intense career of composition and performance at the keyboard. It contains "lateness" by default. We need not assume that the work itself is "transcendental" to see that it comes by the concept honestly.

It is practical to recognize that Beethoven's early reputation as a musician was made performing, improvising, teaching and otherwise making noise at the piano. The compositions for which he is now known are inextricably linked with his uncanny ability to improvise for an audience—a physically musical act. While we can hardly imagine what sort of economic and social forces he must have navigated as a Napoleonic-era artist, it is not hard to say that his actual, uncomfortable presence in the houses of the wealthy (who would be students, benefactors and objects of affection) was crucial to his practical well-being. To put it more broadly: Beethoven’s life and career were made through physical, manual and social contact, centered around and defended by the piano. The abstract life of a ‘composer’ was not an option. He worked through his friends, through his fingers, and of course through his ears.

But this life of closeness to society, to sound and to musical instruments became distorted as he lost his hearing. And it is the disappearance of sound from Beethoven’s life which most completely defies any simple instinct toward sentimentality or cynicism. The loss of hearing would be a life-altering and dark loss for anyone; a sharp encounter with disappearance and distance. When Beethoven was writing ‘late’ works, he wasn’t very old—he was, however, disappearing from the audible and sociable world. When he began to write the Op. 111 Sonata, he was only fifty years old, and he did not die until seven years later. Beethoven had no choice but to learn how to say farewell to things, and—in ways he must have been somewhat aware—this sonata deals with the simultaneously transient and transcendent nature of musical material. It is a work which bids farewell to its own sounds.

This disappearance is of course easier to hear in the second movement, because the second movement (by default, again) is at the end. But the first movement struggles as well. The pianist Andras Schiff speaks of an ‘after-the-storm’ feeling as the first movement ends (in a very fine concert/lecture available through the Guardian), and there is certainly something powerful in hearing how the stormy composer of storms (as in the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony or the String Quintet) writes of a storm’s receding. But it is the second movement which brings us to consider the nature and end of the musical material itself.

Maybe it’s a bit much—a bit Germanic—to repeat the words of Thomas Mann, steeped as he is in his own myths, histories and ironies, but he does provide a strong sense of how this particular work has lived in the view of historians of European classical music. He gives the words to the character of Wendell Kretschmar, who delivers them in a lecture:

Maybe it’s a bit much—a bit Germanic—to repeat the words of Thomas Mann, steeped as he is in his own myths, histories and ironies, but he does provide a strong sense of how this particular work has lived in the view of historians of European classical music. He gives the words to the character of Wendell Kretschmar, who delivers them in a lecture:

He sat on his revolving stool,... and in a few words brought to an end his lecture on why Beethoven had not written a third movement to op. 111. We had only needed, he said, to hear the piece to answer the question ourselves. A third movement? A new approach? A return after this parting – impossible! It had happened that the sonata had come, in the second, enormous movement, to an end, an end without any return. And when he said 'the sonata', he meant not only this one in C minor, but the sonata in general, as a species, as traditional art-form; it itself was here at an end, brought to its end, it had fulfilled its destiny, resolved itself, it took leave – the gesture of farewell of the D G G motif, consoled by the C sharp, was a leave-taking in this sense too, great as the whole piece itself, the farewell of the sonata form. |

The lecture, about leaving a form behind, leaves questions on a few levels—not only for its bemused (and fictional) attendees, or for Thomas Mann’s highbrow 20th-century readers, but also for us, generations later, reading online: what is or was traditional? what was left behind? what is a sonata, exactly? why did it have to die, and what does it matter? The further away we drift from both the context of Beethoven and the context of Thomas Mann, the stranger the arguments seem. If you read too closely, the only part that seems to make real sense is the "revolving stool"—and yet the notions of ending and loss remain important, even when viewed through Thomas Mann's curiously archaic intellectualism.

So the piece remains, as it is, as it was: sound. Irony and skepticism are of course possible, but hardly seem worth the effort. We have all wondered what it means for material to disappear, and here is one memorable rendering—an invisible rendering—of disappearance. There is a sense at the end of the sonata that Beethoven’s own contact with music was coming to an end. Without doubt, the Piano Sonata, Op. 111 does mark a few endings: the end of Beethoven's sonatas for piano; the end of music at his fingertips; the end of music he could personally give. Perhaps it's sufficient merely to recognise the feeling of a former performer (not a deep feeling, necessarily—how could we know such a thing?), for whom contact of fingers with instrument would soon cease to feed back to the ears.

And even this loss, the simple loss of material and personal contact, is a serious enough matter to write about, in sonata form, or whatever form might best carry its theme.

So the piece remains, as it is, as it was: sound. Irony and skepticism are of course possible, but hardly seem worth the effort. We have all wondered what it means for material to disappear, and here is one memorable rendering—an invisible rendering—of disappearance. There is a sense at the end of the sonata that Beethoven’s own contact with music was coming to an end. Without doubt, the Piano Sonata, Op. 111 does mark a few endings: the end of Beethoven's sonatas for piano; the end of music at his fingertips; the end of music he could personally give. Perhaps it's sufficient merely to recognise the feeling of a former performer (not a deep feeling, necessarily—how could we know such a thing?), for whom contact of fingers with instrument would soon cease to feed back to the ears.

And even this loss, the simple loss of material and personal contact, is a serious enough matter to write about, in sonata form, or whatever form might best carry its theme.

© Timothy Summers