Audio & Insight |

Beethoven Sonata for Piano, Op. 111, mvt. 2 — Arietta — Adagio molto semplice e cantabile |

Variations almost invariably begin with what is simple. How they end is another matter, which can be variously treated.

This page traces the theme and variations in the last movement of Beethoven's last piano sonata, Op. 111. There is no simple way to summarize this work quickly, but there are a few elements which are indeed simple, even if they have implications which are not easy to describe, about how it grips and how it lets go.

The audio players contain measurements of harmonic content in the live audio, coloring harmonies which are close to one another in harmonic function close on the visible spectrum. If you would like to learn more about these audio players, click here.

This page traces the theme and variations in the last movement of Beethoven's last piano sonata, Op. 111. There is no simple way to summarize this work quickly, but there are a few elements which are indeed simple, even if they have implications which are not easy to describe, about how it grips and how it lets go.

The audio players contain measurements of harmonic content in the live audio, coloring harmonies which are close to one another in harmonic function close on the visible spectrum. If you would like to learn more about these audio players, click here.

Theme

The theme is a kind of hymn or chorale, though it is marked Arietta, as if it were merely a little song. It's slow enough (Adagio) to be slightly hard to hear and to remember as its own little piece, but it is worth keeping in your ear, because—dense though the following variations are—it remains deeply present in all that is to come. Beethoven's instructions Semplice (simple) and Cantabile (singing) are useful to bear in mind, too.

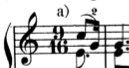

The main motive—the first set of sounds—sticks around, and is worth identifying. It gives the theme a sense of ceremony and motion. Its notes could have a word or two placed upon them like a lyric or motto, but they may prove most memorable if they are left to build a merely musical identity.

Variation 1

The first variation makes use of the motion inside of the main motive, placing it onto every beat, so that each beat becomes a pickup to the next. The piece still moves gently. The melody has an extra note (an A on the downbeat), which gives it a bit more color, too. But mainly, this first variation stays fairly close to its thematic source, growing it simply and lyrically.

Variation 2

The second variation does something similar, but doubles the speed of the motive, which is at once a simple strategy and a destabilising force. The pickup motive now happens twice in every beat, which is lightly excessive.

But the mood remains (as indicated) dolce. The harmony is stretching a little toward the sharp side (a bit more blue at the beginning), which gives a slight edge or brightness.

But the mood remains (as indicated) dolce. The harmony is stretching a little toward the sharp side (a bit more blue at the beginning), which gives a slight edge or brightness.

Variation 3

Then it redoubles. The pickup to the first bar of the third variation now has four pickups inside of it. The consequence is something in the area of ecstatic or manic. The marking l'istesso tempo (the same tempo) seems to insist that the pressure of the doubling note-speeds grows without any allowances for increasing difficulty. Tiny note-values combined with an Adagio tempo make the piece seem slow and fast at the same time. (This slow-fast confusion is also evident in the crazy time signature, 12/32.)

Variation 4

The apparent plan of infinite note-halving clearly cannot go on forever. Even visually, this is clear: every one of the the printed excerpts on this page (including this one) contains the same amount of music—an upbeat and two beats following—and by now the variations have become too heavy with invention and ornament, to fit in memory or even on a page.

So here in the fourth variation comes a kind of formal collapse. Down beats in the theme are empty, which profoundly upsets the orientation of the listener. The left hand just sits and grumbles, while the notes of the theme become fraught with appoggiaturas. There is no simple repeat in the variation - instead there is a sort of inverted experimentation, where the music flies high into the air. By the end of the repeat of the B section, the theme has evaporated, or perhaps sublimated.

So here in the fourth variation comes a kind of formal collapse. Down beats in the theme are empty, which profoundly upsets the orientation of the listener. The left hand just sits and grumbles, while the notes of the theme become fraught with appoggiaturas. There is no simple repeat in the variation - instead there is a sort of inverted experimentation, where the music flies high into the air. By the end of the repeat of the B section, the theme has evaporated, or perhaps sublimated.

|

|

And the music just stays there, up in the air. It sits in its texture, enjoying the pure tonality, along with some inconsequential fragments of theme and an apparent absence of gravity.

|

|

|

There comes a kind of satisfaction in the wandering.

|

|

|

There comes a hint of a variation made only of arpeggios.

|

|

|

The opening figure finds more and more contexts, surrounded by trills, essentially free of identifiable relationship to a larger theme...

|

|

|

Until suddenly the continuation of the theme appears, but in an uncomfortable harmonic context, and without an ability to find the end of the phrase, or of anything.

|

Variation 5

|

|

And then there it is, with no need for repeats. The motion in the left hand gives power. And tells that what we know as the end of the phrase...

|

|

|

...is not in fact the end of the phrase. There comes a discovery of new implications of the theme. Finding new ways not-to-end, and to rise.

|

Theme

|

|

The theme comes back, but has no need for a second half any more.

|

|

|

The motive alone becomes sufficient.

|

|

|

And then in the end mere motion is sufficient. A tonality; fragments; nothing. The motive builds itself a small monument, as though remembering who it is. A pile of bricks. Even the absence of motion is sufficient, and it can end.

|

© Timothy Summers