NOTES & STORIES |

Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 30 in A Major, Op. 109 |

“Only once in his life was one of his piano sonatas played in a public concert”

—from Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Jan Swafford, p. 34

(which quotes: The spirit of Mozart from Haydn’s Hands, Elaine Sisman, p. 46)

—from Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Jan Swafford, p. 34

(which quotes: The spirit of Mozart from Haydn’s Hands, Elaine Sisman, p. 46)

As an inhabitant of the 21st century, one might have to read the above quote twice to begin to get a feel for how utterly different the context for music in Beethoven’s time must have been, and how far from the ever-raging context of now. In reading this statement, or quoting it, one might feel a compulsion to check its source. But it seems to be true enough, and significant. Music on the piano-sonata scale--chamber music--was a fairly private matter in the early 19th century. Not a small matter, necessarily, but certainly a private one. A piano sonata was a book of music to be read and studied. It was a gift to be offered to a lover of music, and then published for reading and playing in the private home. A great many pieces—even up to the Goldberg variations of Bach—were études or clavierübungen: piano studies. A "sonata" might be taken simply as a piece of sound, a bit more poetic in its outlook than an étude, for the household.

|

In the case of our current performance context—our digital context—one might also wonder if the presentation of a work such as Beethoven's Op. 109 online is as much a return to the work’s origin as it is a departure. Virtual presentation is a far cry from live performance. But a sense of privacy, along with a sense that a piece of music is also a kind of literary (etymologically ‘Romantic’) work, is perhaps increased. One might study the piece a while, and then get a coffee. One might find some interesting moment in the work, repeat it, and then let it go for a while. Or maybe the phone rings. But then one can return, because the music contains a lot of… something. Let us call it information. And it will still be there when you return: complete, silent, resonant, ready - lines and dots, bits and bytes.

|

(Aside: this idea of ‘privacy’, of course, excludes that, because you are reading this, you are now more likely to encounter more advertisements for Beethoven-related products and other items relevant to the Beethoven-demographic. But that is a discussion for another day.)

|

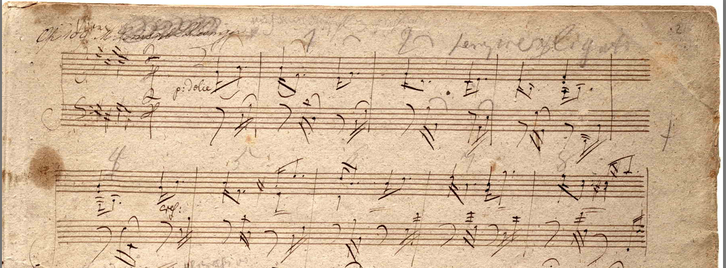

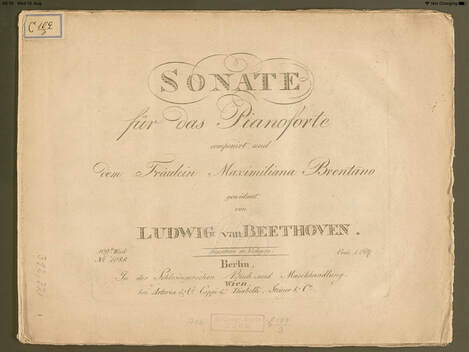

The Sonata Op. 109 in E major was written for Maximiliane Brentano, the 18-year-old daughter of Beethoven-friend, Immortal-Beloved-candidate and all-around force-of-nature Antonie Brentano. It seems to have had its origin in a sketch for a piano etude, but Beethoven later repositioned his initial fragment of music as the beginning of a sonata. (This fine discovery belongs to the British musicologist Nicholas Marston). The opening is quite lovely to hear this way--its opening figures a casual gift for a young musician of eighteen years. But the work quickly takes on a kind of willfulness, or consciousness, or doubt. When the opening figures return after a cadenza-like episode, the unbothered spirit of "etude" becomes elusive. There is a sense of lurking necessity, and of a search for orientation. After bar eight of the first movement, the sense of the everyday at home is no longer the same.

As the everyday context of performance itself changes radically before our eyes--or at least seems to be doing so during these months of quarantine in 2020—it is worth considering how the contours of the history of performance, presentation, and music-reading may have transformed a piece like this from being a personal gift to being a cultural touchstone.

Although he was lonely, eccentric and unruly, Beethoven was famous, and was an iconic musical figure. (He was "one of the most sought-after musicians of his generation," to put it in the tortured parlance of our time.) One musician who sought him out was the eleven-year-old Franz Liszt. The story which Liszt tells of this meeting concludes with a kiss from Beethoven and a kind of musical benediction, to which he attached a great importance. "This was the proudest moment in my life--the inauguration to my life as an artist. I tell this very rarely--and only to special friends." There is no absolute evidence that the meeting took place as Liszt describes, but there’s no need to be cynical or dismissive about the story. Liszt’s teacher Czerny (a student of Beethoven whose own piano exercises move pianists’ fingers to this day) would certainly have made an effort to arrange such a meeting on behalf of his fantastic young student, and any eleven year old would have been overwhelmed by any attention from such an eminently eminent musician as Beethoven--no matter whether that meeting involved a kiss or not. And it was indeed Franz Liszt who would bring the sonatas of Beethoven to a large public.

Although he was lonely, eccentric and unruly, Beethoven was famous, and was an iconic musical figure. (He was "one of the most sought-after musicians of his generation," to put it in the tortured parlance of our time.) One musician who sought him out was the eleven-year-old Franz Liszt. The story which Liszt tells of this meeting concludes with a kiss from Beethoven and a kind of musical benediction, to which he attached a great importance. "This was the proudest moment in my life--the inauguration to my life as an artist. I tell this very rarely--and only to special friends." There is no absolute evidence that the meeting took place as Liszt describes, but there’s no need to be cynical or dismissive about the story. Liszt’s teacher Czerny (a student of Beethoven whose own piano exercises move pianists’ fingers to this day) would certainly have made an effort to arrange such a meeting on behalf of his fantastic young student, and any eleven year old would have been overwhelmed by any attention from such an eminently eminent musician as Beethoven--no matter whether that meeting involved a kiss or not. And it was indeed Franz Liszt who would bring the sonatas of Beethoven to a large public.

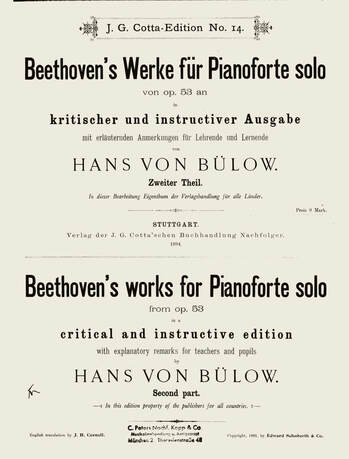

The tangle of names and relationships which follow Liszt is so dense as to defy description, but, insofar as it can be clear, it centers around the figure of Hans von Bülow. Von Bülow was a student of Friedrich Wieck, who was the father of Clara Wieck, who married Robert Schumann. Von Bülow married Liszt’s daughter Cosima, who later left him for Richard Wagner. Von Bülow was conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic from 1887, and he is memorialized on the wall just backstage (the cafeteria wall) along with Richard Strauss, Arthur Nikisch, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Leo Borchard, Sergio Celibidache, Herbert von Karajan, and Claudio Abbado. Von Bülow heavily promoted the music of Johannes Brahms. He played the premiere of Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1, on October 25, 1875, in Boston, Massachusetts. And last but not least, von Bülow was the first to perform a complete cycle of Beethoven sonatas--a project which brought the idea of ‘canonicity’ squarely into the world of performance.

Von Bülow left behind a remarkable edition of the Beethoven sonatas as well: a “Kritischer und instructiver Ausgabe Mit erläuternden Anmerkungen für Lehrende und Lernende": a "critical and instructive edition with explanatory remarks for teachers and pupils.” His instructions and explanations are both musically thorough and thoroughly Romantic. For example:

It will hardly be construed as a straying on the Editor’s part into the province of “program-music” if he recommends, as the best guide to the beautiful delivery of this masterpiece of polyphonic (imitative) song, the recalling of Goethe’s words in the first monologue of Faust:

Wie Himmelskräfte auf- und niedersteigen

Und sich die gold’nen Eimer reichen!

How powers celestial, rising and descending,

Their golden buckets ceaseless interchange!

(Anna Sawanwick’s translation, London, Bell and Daldy

Not only did von Bülow present Beethoven’s works in a canonical format, both on stage and on paper; he also brought the rest of the canon to join Beethoven. His edition was published by Cotta, which held a monopoly on publishing the works of Goethe and Schiller until 1867. To quote Goethe in a Cotta edition of Beethoven was an utterly natural gesture for the entwined and entwining notion of Kultur und Bildung in post-Napoleonic Germany. Somehow, it all fit together on a shelf.

The twentieth century brought the piano sonatas into a new canon of discography. "Interpretation" from a performer was no longer a matter of putting out a poetically learned edition or giving a "recital" (funny word, "recital"...); it was a matter of adding to the audible record, on what became known, pithily, as a "record."

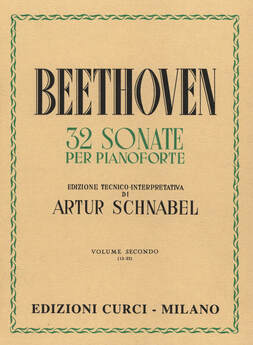

Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) made the first complete recording of the Beethoven sonatas, and thereby provided Beethoven's works a second entrance to the private sphere, this time as canonical LPs. Schnabel could trace his interpretive lineage directly to Beethoven: his teacher Teodor Leschetizky studied with Carl Czerny, who was (again) the teacher of Liszt and who was a student of Beethoven himself. Schnabel left Germany in 1933 for the usual reasons. He taught at the University of Michigan, and developed a friendship with fellow expatriate Arnold Schoenberg. His 1935 recording of the complete Beethoven Sonatas was entered into the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in 2018.

Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) made the first complete recording of the Beethoven sonatas, and thereby provided Beethoven's works a second entrance to the private sphere, this time as canonical LPs. Schnabel could trace his interpretive lineage directly to Beethoven: his teacher Teodor Leschetizky studied with Carl Czerny, who was (again) the teacher of Liszt and who was a student of Beethoven himself. Schnabel left Germany in 1933 for the usual reasons. He taught at the University of Michigan, and developed a friendship with fellow expatriate Arnold Schoenberg. His 1935 recording of the complete Beethoven Sonatas was entered into the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in 2018.

Meanwhile, in Germany (to which Schnabel never returned), Wilhelm Kempff (1895-1991) made two sets of recordings of the complete sonatas, and passed the tradition still further, very notably to his student Mitsuko Uchida, who is now the head of the Marlboro Festival in Vermont.

The co-founder of Marlboro, Rudolf Serkin, was also regarded as one of the great interpreters of the Beethoven piano sonatas. Serkin brought the German-Bohemian musical tradition squarely to the center of American classical music life, serving as director of the Curtis Institute of Music in the sixties and seventies, and running Marlboro with Pablo Casals and Adolf Busch. (A curious view on the Marlboro-ish atmosphere, and its uncomfortable place in American culture, can be seen in Five Easy Pieces, with Jack Nicholson.) Serkin, like Schnabel, was a Jewish emigré. He, too, studied composition with Schoenberg, though much earlier, in Vienna. And he, too, profoundly influenced generations of students of classical music.

The co-founder of Marlboro, Rudolf Serkin, was also regarded as one of the great interpreters of the Beethoven piano sonatas. Serkin brought the German-Bohemian musical tradition squarely to the center of American classical music life, serving as director of the Curtis Institute of Music in the sixties and seventies, and running Marlboro with Pablo Casals and Adolf Busch. (A curious view on the Marlboro-ish atmosphere, and its uncomfortable place in American culture, can be seen in Five Easy Pieces, with Jack Nicholson.) Serkin, like Schnabel, was a Jewish emigré. He, too, studied composition with Schoenberg, though much earlier, in Vienna. And he, too, profoundly influenced generations of students of classical music.

How curious it is to see all of these old editions, these suddenly-aged artifacts of the same sonatas. To see them is to see time knocking off their ornamental corners as they proceed (Darwin-cartoonishly) toward the regal crimson Bärenreiter Urtext, which gives the seductive and deceptive impression that purity and origin could be united. The names of the interpreters, the names of the dedicatees, the names of the editors, the publishers, they fade as the bony urtext appears. And now with our international-style urtext editions--so close and so far from the manuscript-- here is the text--but where is the context?

Since the 1970s, classical music has seen an enormous and beautiful increase in the study of historical context--of the instruments, sources, and influences of both a work and its time. The fruits of these studies might be heard, for example, in the work of pianist and musicologist Robert Levin. But even this movement has faded, now that "now" can be so exhaustively and bewilderingly documented. Under these information conditions, all contexts have come to seem equal in importance, influence, and information.

Since the 1970s, classical music has seen an enormous and beautiful increase in the study of historical context--of the instruments, sources, and influences of both a work and its time. The fruits of these studies might be heard, for example, in the work of pianist and musicologist Robert Levin. But even this movement has faded, now that "now" can be so exhaustively and bewilderingly documented. Under these information conditions, all contexts have come to seem equal in importance, influence, and information.

Leon Fleisher (left) -- pianist, conductor, educator, and student of Artur Schnabel -- with President George W. Bush, First Lady Laura Bush, and 2007 Kennedy Center honorees Martin Scorsese, Diana Ross, Brian Wilson, and Steve Martin. White House photo by Eric Draper - Public Domain

Leon Fleisher (left) -- pianist, conductor, educator, and student of Artur Schnabel -- with President George W. Bush, First Lady Laura Bush, and 2007 Kennedy Center honorees Martin Scorsese, Diana Ross, Brian Wilson, and Steve Martin. White House photo by Eric Draper - Public Domain

We are confronted now with a kind of Übertext—all the documents and histories and anecdotes and recordings and videos of graduation recitals swirling around any piece of music. And what seems important now is that a performer can give an impression of contact, of a moment which is real even inside this infinite, ubiquitous, and untouchable matrix of representations. This contact is the real complexity, the absolution of information.

In the present case, with a performance of the piano sonata Op. 109, performed in August 2020 in Neukölln, Berlin, and broadcast online to wherever it may be viewed, we must still somehow acknowledge that we work within a history of performance stemming from a possible exaggeration by the undeniable Franz Liszt: that he met Beethoven, and that Beethoven blessed his life.

In the present case, with a performance of the piano sonata Op. 109, performed in August 2020 in Neukölln, Berlin, and broadcast online to wherever it may be viewed, we must still somehow acknowledge that we work within a history of performance stemming from a possible exaggeration by the undeniable Franz Liszt: that he met Beethoven, and that Beethoven blessed his life.

© Timothy Summers