Notes & Stories |

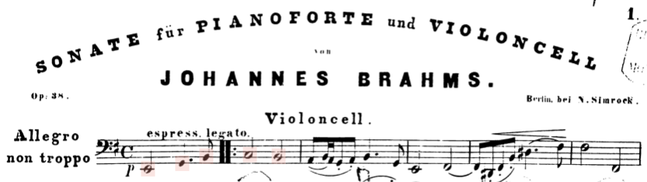

Johannes Brahms: Sonata for Cello and Piano No. 1 in E minor, Op. 38 |

With the Cello Sonata, Op. 38, of Johannes Brahms, the pleasure of sound, especially the warmth of the cello, can be the starting point and the ending point. Of course there are pleasures in harmonic combinations, pleasures in musical predictions, and pleasures in memories and associations. And of course there are the now-distant pleasures of listening in a room with other people. But previous to all of these possibilities is the pleasure of the sound itself.

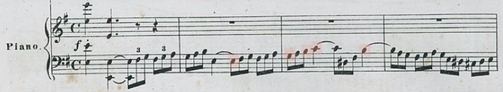

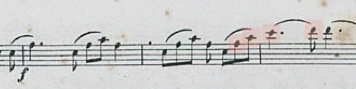

Example 1 - opening theme, contour highlighted

Example 1 - opening theme, contour highlighted

Born in chilly Hamburg in 1833, Johannes Brahms had an instinct for warmth in sound: horns, cellos, cello sections, clarinets, violas, men’s choirs. Something in the lower register, something broad and yet suggestive of an interior — something poco forte (‘a little strong’) as he often wrote – would bring forth music very particularly his own. With only pen in hand, he could trace a feeling of richness in which dense content could find earth and sense. Brahms' vast compositional technique could thrive in this sonic climate: an atmosphere warm enough to allow intensive musical development, while never demanding that concepts precede understanding.

This is not to say that there aren’t abstractions. There are beautiful musical systems, beautiful to consider. A great deal of what happens in the thirty-odd minutes of the Op. 38 cello sonata, for example, arises from the contour of its first five notes, which outline a rising triad in the cello with a flat sixth atop it, coming back to rest on the fifth (see the notes marked red in example 1, above).

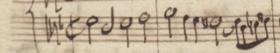

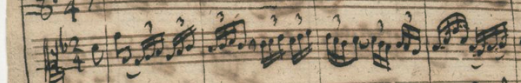

Example 2 - second theme, contour highlighted

Example 2 - second theme, contour highlighted

This motive reappears soon after the opening, transformed. The second theme, carrying an utterly different mood, bears within it the same melodic outline (example 2). This balance between similarities of material and difference of mood makes powerful music, and is not just a parlor trick. Hearing similarity, we can know where we are; hearing difference, we can know that we are not where we used to be. Here in the first movement of the cello sonata, it is as though the depths of the opening theme are being fought, overcome, or lifted by the second theme. However one might describe it, the change of mood between themes is absolutely clear, precisely because the two melodies make use of the same music. It is powerful to recognize that these similarities, contrasts, and conflicts create drama, meaning, and memory.

|

Additionally, it is no coincidence. The small rising motive with a flat note atop it persists through the piece. The second movement carries the same melodic motive within it (example 3), though distant in key and in feel. The third movement, too (example 4, below), outlines the same pitches, decorated by running triplets.

|

|

Of course, there are definite limits to this type of analytical reduction, as Brahms was well aware. He once gave a gruff response to a critic named Schubring (reportedly a very insightful advocate), who had similarly analyzed motives in the German Requiem:

|

I disagree that in the third movement the themes of the different sections have something in common…. If it is nevertheless so… I want no praise for it…. If I want to retain the same musical idea, then it should be clearly recognized in each transformation, augmentation, inversion. The other way around would be a trivial game and always a sign of the most impoverished imagination.

(from Johannes Brahms, A Biography, by Jan Swafford, p. 234)

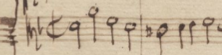

Example 5 – J.S. Bach: Contrapunctus XIV from 'Art of Fugue'

Example 5 – J.S. Bach: Contrapunctus XIV from 'Art of Fugue'

Brahms' objections notwithstanding, we are forced to admit that the matter of this motive extends far outside the cello sonata, though, because it contains its own non-trivial musical history. This is no ordinary theme. The last movement of Brahms' sonata, with its triplet decorations, is without doubt a reference to the Contrapunctus XIV (example 5) from Bach’s Art of Fugue. This in turn indicates that the first movement must also derive from Bach’s work, and therefore that the entire cello sonata stands upon an upside-down version (example 6) of the main theme (example 7) of Johann Sebastian Bach’s crowning contrapuntal study. Knowing this changes the way the piece is heard, and the way it's played, and thus the way it sounds and becomes real. The reference to Bach has a palpable meaning and sensation.

In the end, the cello sonata, Op. 38, creates a means to provide not only the pleasure of sound, but also the pleasure of study, analysis, reading, memory, and note-encoded history. The musical fragments — these systems, these motives, these touchstones — join together to indicate much more than the sum of their parts. Brahms was driven by the potential for a pleasure beyond what could be heard, not restricted to the content and play of compositional systems. The most extraordinary and transformative moments of his music are often the quietest, as though they pointed toward something that defied description or systematization — something not forte or even poco forte, but simple, pianissimo, full of silences and simplicities.

Lastly, lest one become lost in the encompassing sound of what’s written for the extraordinary object known as a ‘cello’, there is the sound of the piano. The keyboard provides all of the identities, impacts and harmonies in which the cello music becomes embedded and interwoven. Behind the warmth of the cello is the tapestry of the piano sound: its multiplicity, its harmonic definitions, its complexity, its resonance. Brahms himself would have been the one at the piano, devising the ways in which his symbols and mottos might become audibly woven into motion, texture and time. His piano would have been different from the modern piano — more transparent, more contrapuntal, but the sonic area it could define would be no less broad. The atmosphere is in the systems; the systems are in the atmosphere, both full with sound; and through all this interplay, it comes to seem as though something might truly live. An instrument, a work, a performer, an author, a reader, a sound, an experience of fullness, all in the alpha and omega of the here and now.

© Timothy Summers