Notes & Stories |

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Passacaglia from Rosary Sonatas |

Passacaglia: the minimum of formEven at its simplest, music remains stubbornly irreducible. It relies entirely upon patterned thinking, yet always pushes at the very idea of 'pattern'. Even the sound of a single note is by definition filled with infinite component elements; and in listening to sounds, our own minds make wild branches of inferences and connotations from what we hear. The complexities are infinite both in physical fact and in perception. So when we spot and follow an identifiable musical path – when we do any musical 'analysis' – we inevitably find that we can trace only the faintest outline of what we experience. To identify a musical pattern may open a whole field of expectations, and that may sharpen the intensity of listening. But measurements and predictions are inevitably overwhelmed by the sensations and possibilities of sound itself.

|

The passacaglia stands among the clearest of all musical forms -- basically, it's a loop in the bass. But a passacaglia bursts with musical potential. It develops inevitably, almost unconsciously, as it repeats. An Italian word with Spanish roots, passacaglia means 'walking the street' (pasar => walk, calle => street). This translation suits the musical sensation: a passacaglia can seem to create a process as sure as footsteps – one after another, yielding ever-shifting impressions. Such a pattern is easy to hear: you might not 'analyze' it any more than you might analyze a sidewalk. Nevertheless, a rich scene of narrative and ornament can develop, much as your own feet, one after the other, can take you to see the world. Some paths, for whatever reason, yield more richly than others. Biber's Passacaglia walks a rich path.

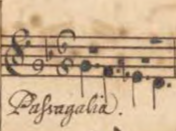

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber's Passacaglia is one of the oldest surviving solo violin works, a distinction no doubt supported by the absoluteness of its musical process: it walks over four notes. Arising from these notes, and rising above them, a second voice begins to express itself, adding dimensions, perspectives, and a sense of linear narrative above the cycles.

The landscape which emerges has a few definable sections, each marked by the reappearance of the bass line on its own:

The landscape which emerges has a few definable sections, each marked by the reappearance of the bass line on its own:

|

Introduction: the falling bass line alone sets the piece in motion; a durable melodic voice evolves, culminating in a kind of chorale.

|

|

Expansion: the bass line alone brings more active patterns and reaches a full choral-melodic close.

|

|

Decoration and Ascension: the bass line alone brings experiments in fast ornamentation, then in a slow adagio, and finally skips up an octave.

|

|

Brightness in Major: the bass line alone (one octave higher) replicates itself at the interval of a sixth below and brings the work into a major key area.

|

|

Pause and Return of Minor: a hint of the very opening melody brings the piece back to minor.

|

|

Sublimation: the bass line alone brings rapid ascents and descents, then settles around a single note, becomes blurry and returns to a familiar choral-melodic music.

|

|

Cadence: the passacaglia line resolves, major.

|

The bass line is always there. One might almost call it simple, and yet... it is not simple. Simple rules need not define a simple outcome, and in this case, the musical result has elements not only of complexity and expansion, but of what may safely be called glory.

Church Context: Rosary Sonatas

Rich and dense though its musical content may be, Biber's Passacaglia also suggests a much larger musical, historical, and above all ecclesiastical context. It walks no ordinary narrative path. The Passacaglia appears after fifteen other Rosary Sonatas (or Mystery Sonatas), programmatically religious works which Biber wrote in three cycles: five Joyful Mysteries, five Sorrowful Mysteries; and five Glorious Mysteries. Taken as a set, these sonatas make a curiously encyclopedic collection for the violin, treating various string tunings as sonic/iconographic symbols for each piece. Generally speaking, the Joyful Mysteries are tuned tighter and brighter and the Sorrowful Mysteries looser and darker. Even without going into the details of it, it is still interesting to see how much trouble Biber took to place religious meanings in the body of the instrument itself. In the Rosary Sonatas, the physicality of the instrument plays its own role, as both a body and a symbol.

As the last of the Rosary Sonatas, and as the only piece without continuo accompaniment, the Passacaglia is often performed separately from the other works of the set. Its bass line seems perhaps to have been derived from a hymn to the guardian angel – the piece contains both its own accompaniment and its own protection. Convenient instrumentation, simple form and programmatic undertones have won the Passacaglia a permanent place in the violin repertoire since its re-discovery in 1905 at the Bavarian State Library in Munich.

Each of the Rosary Sonatas is preceded by an engraving in the manuscript (they are sometimes even referred to as the 'copper-engraving sonatas'). The image at the beginning of the passacaglia seems to indicate that the possible reference to a guardian angel in the bass line is a meaningful starting point for giving the work a reading or a hearing.

Beyond all that... beyond the analyses and iconographies... there remains also the open road of simply playing the fiddle. A path to walk and to hear and to give our attention – on the course of which we all might use a bit of protection, now and again.

Each of the Rosary Sonatas is preceded by an engraving in the manuscript (they are sometimes even referred to as the 'copper-engraving sonatas'). The image at the beginning of the passacaglia seems to indicate that the possible reference to a guardian angel in the bass line is a meaningful starting point for giving the work a reading or a hearing.

Beyond all that... beyond the analyses and iconographies... there remains also the open road of simply playing the fiddle. A path to walk and to hear and to give our attention – on the course of which we all might use a bit of protection, now and again.

© Timothy Summers